E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) with Acute Respiratory Failure in Three Adolescent Patients: a Clinical Timeline, Treatment, and Product Analysis

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13181-020-00765-9

Abstract

Introduction

E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI) has become a recent concern among public health officials. Factors that contribute to the concern include an increasing number of cases over time, the severity of the illness, and an unknown understanding of the pathophysiology and etiology of the illness.

Case Series

We cared for three adolescent patients with acute respiratory failure secondary to EVALI. All three patients were treated with high-dose steroids in addition to antimicrobials, which resulted in clinical improvement and resolution of their respiratory failure. Pulmonary function testing was performed on these previously healthy patients both acutely and subacutely. Additionally, we report the results from the laboratory analysis of one vaping device fluid which revealed previously unpublished components within these products.

Discussion

EVALI is a recent public health concern without a known etiology which can cause life-threatening lung injury in patients without prior lung pathology. We hope these cases will highlight the importance of return precautions in adolescents with vague respiratory symptoms and provide a cautionary tale to providers while they counsel patients regarding the use of these products.

Introduction

E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI) has become a recent alarming public health concern [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Factors that contribute to the concern include an increasing number of cases over time, the severity of the illness, and an unknown understanding of the pathophysiology and etiology of the illness. Although a single etiology and the mechanism of toxicity are not known, patients tend to have a similar clinical course, starting with initial malaise and vague gastrointestinal symptoms, with a subsequent development of cough, dyspnea, and fevers. The patients can develop radiographic findings of bilateral pulmonary opacities [9], and they can progress to respiratory failure in severe cases. Herein, we report three recent cases of EVALI, all of whom initially reported to an outpatient clinic and were diagnosed with pneumonia, before progressive deterioration required admission to our Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). None of the three patients had prior lung pathology. They were treated with high-dose steroids, had pulmonary function testing at the day of discharge, and quantitative analysis was completed on one of the products. All three patients and their parents provided verbal and written consent for this report; this case series was deemed exempt by our Institutional Review Board.

Patient 1

A 15-year-old male with no significant past medical history (no prior pulmonary diagnoses and no daily medications) presented with a five-day history of cough progressing to respiratory failure. Due to increasing dyspnea, fevers, and self-resolving diarrhea, he presented to an urgent care clinic where he was found to be hypoxemic with an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 86% on room air. He was subsequently taken to a local emergency department (ED) and admitted to the hospital due to hypoxemia, fever (39.1 °C), tachycardia (132/min), and tachypnea (22/min). He received acetaminophen, nebulized albuterol and ipratropium, and supplemental oxygen. Over the following day, his support was escalated to high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) due to worsening respiratory distress. He was transferred to our PICU after receiving ceftriaxone and azithromycin for a working diagnosis of pneumonia.

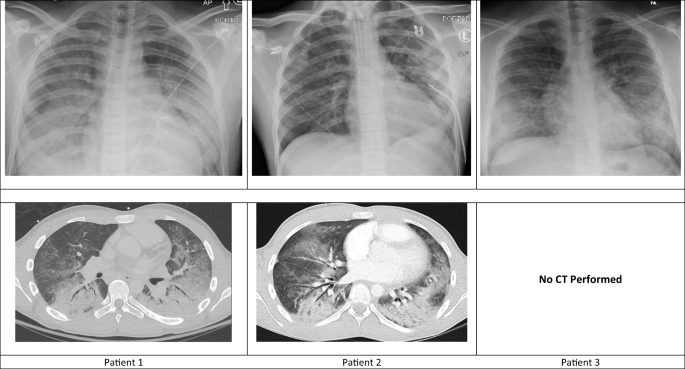

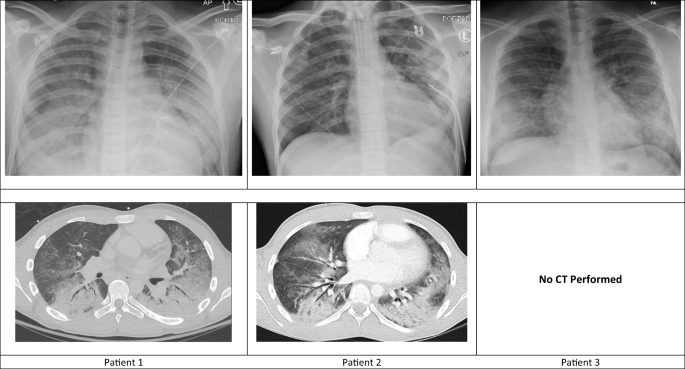

On admission to our PICU he was tachycardic (110/min), normotensive (103/84 mmHg), and afebrile. His respiratory rate was 13/min with Spo2 95% on HFNC 0.5 FiO2 (20L/min). A chest x-ray (CXR) revealed bilateral opacities which had worsened since time of admission (Fig. 1). Further history revealed he was using a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) oil vaporizer (“vape”) almost daily for one year. He used multiple products from multiple sources over this time period. Five days prior to admission, he inhaled from a vape pen and immediately felt a “burning in his lungs” which he had not experienced before.

Fig. 1

Radiographic images of the patients’ lungs early in the course of admission. Top row illustrates the chest x-ray which corresponds to the chest CT images shown in the second row.

A chest CT (computed tomography) was obtained on day 3 of hospitalization, and results showed diffuse central ground glass opacities with air bronchograms most notable in bilateral lower lobes (Fig. 1). His respiratory failure continued to progress, and he was intubated on day 6 of hospitalization (Table 1). He had a negative infectious workup including respiratory pathogen panel (influenza A [includes H1N1/2009]; influenza B; parainfluenza 1, 2, 3, and 4; respiratory syncytial virus A and B; adenovirus; human metapneumovirus; human rhinovirus/enterovirus; coronavirus; Chlamydia pneumoniae; and Mycoplasma pneumoniae), Histoplasma urine antigen and Legionella urine antigen, urinalysis, urine culture, respiratory culture, and blood cultures. A hypersensitivity pneumonitis panel (antibodies directed at Aspergillus fumigatus #1, A. fumigatus #2, A. fumigatus #3, A. fumigatus #6, A. flavus, Aureobasidium pullulans, pigeon serum, Micropolyspora faeni, Thermoactinomyces vulgaris #1, T. candidus, Saccharomonospora viridis, Phoma betae [fungi/mold, IgE], pork [food, IgE], beef [food, IgE], and Animal Feather Mix [IgE]) was also negative. The patient was started on methylprednisolone 30 mg (0.5 mg/kg) IV every 12 hours on the day of intubation (day 5 of admission). His respiratory status improved, and he was extubated on day 16 of hospitalization. He was discharged with a prednisone taper, and outpatient pulmonology evaluation revealed nearly normal pulmonary function testing (PFTs; Table 2).

Table 1 Timeline of relevant vital signs and laboratory results. Vital signs were documented at 07:00 each day. Day 0, Day of methylprednisolone treatment initiation.

HR, Heart rate (beats/min); RR, Respiratory rate (breaths/min)

Mode of support (RA, room air; NC, nasal cannula; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; MV, mechanical ventilation)

FIO2, Fraction of inspired oxygen; SpO2, Peripheral oxygen saturation from pulse oximeter

S/F ratio, Saturation/FiO2 Ratio; P/F ratio, PaO2/FiO2 ratio

OI, Oxygenation index; OI = (FiO2 x PAW)/PaO2

CRP, C-reactive protein (mg/dL)

Table 2 Pulmonary function testing (PFT) for all three cases. All three cases had PFT performed on day of discharge from hospital. Post- bronchodilator challenge not performed for Case 2 or 3. Follow-up PFT not performed for Case 3.

Patient 2

A 16-year-old male with no significant past medical history (no prior pulmonary diagnoses and no daily medications) presented with cough and dyspnea. He reported a headache 6 days prior to admission, for which he used a THC oil vaporizer. He had been vaping multiple products from multiple sources daily for almost 5 months to relieve anxiety. He had an episode of vomiting, fever (38.9 °C), and decreased appetite. He was evaluated by his primary care physician (PCP) after he developed worsening cough, chest tightness, and dyspnea, and was empirically started on azithromycin for clinical pneumonia. His symptoms progressed, and he presented to a local ED 3 days after PCP evaluation where he was found to be afebrile, tachypneic (39/min) with SpO2 94% on room air. CXR and chest CT both showed diffuse bilateral parenchymal and retrocardiac ground-glass airspace disease (Fig. 1). In addition to supplemental oxygen, he received ceftriaxone and 80 mg (2 mg/kg) methylprednisolone intravenously. He was transferred to our ED, where he was found to have progressive tachypnea and hypoxemia that required escalation to HFNC, and admission to our PICU.

His respiratory status continued to deteriorate, and he was intubated on day 2 of hospitalization (Table 1). Methylprednisolone (80 mg every 12 hours) and antibiotics (7 days of ceftriaxone and vancomycin) were continued. He had a negative respiratory pathogen panel (same as patient 1), urinalysis, urine culture, respiratory culture, and blood cultures. His clinical status and CXR findings improved, and he was extubated on day 8 of hospitalization. He was discharged on hospital day 12 with steroid taper. PFTs were relatively normal (Table 2).

Patient 3

A 17-year-old male with no past medical history was admitted to our PICU for progressive respiratory distress. The patient reported vaping daily, using a variety of products and devices, for almost 2 years with the majority of his use being with a THC oil vaporizer. Eight days prior to admission, he reported taking numerous extra puffs from his THC vape device and immediately felt unwell. He described a slight burning of his lungs, followed by 2 days of vomiting. As these symptoms improved, he developed a cough and dyspnea. He was evaluated by his PCP and started on azithromycin for bronchitis. His symptoms progressed, and he reported to a local ED where he was subsequently admitted for pneumonia. His respiratory status worsened despite treatment with ceftazidime, and he was transferred to our PICU on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on day 1 of admission at the local hospital.

Upon arrival, he was afebrile, tachypneic (37/min) with SpO2 96% on HFNC 1.0 FiO2 (20 L/min), and tachycardic (104/min). A CXR obtained immediately after transfer showed diffuse ground-glass lung opacities more prominent in bilateral lower lobes (Fig. 1). His support was escalated to 30 L/min HFNC within 12 hours of admission. He was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 80 mg (0.6 mg/kg) every 12 hours on the day of admission and prior to transfer. His clinical status significantly improved over the next 48 hours along with improvement in CXR findings, and he did not require intubation. His respiratory support was weaned to room air by day 3 of hospitalization. He had a negative respiratory pathogen panel (same as patient 1) and respiratory culture, and his antibiotics were discontinued on day 4. He was discharged home on hospital day 4 with oral steroid taper. PFTs were relatively normal (Table 2).

Laboratory Analysis of Vaping Device

Patient 1 presented their used THC-vaping product for analysis. The testing was limited due to the quantity of remaining product. As such, we prioritized the analysis to pesticides while also evaluating for the vitamin E which had been found in recent cases [10]. Using previously validated methods at the Iowa State Hygienic Laboratory, bifenazate (13 ppm), boscalid (0.14 ppm), and tebuconazole (0.73 ppm) were detected quantitatively (via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [LC-MS/MS]), and cannabinoids and vitamin E acetate were detected qualitatively (via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry). We will defer discussion of aflatoxin and cannabinoids as these are not known to cause acute tissue damage and their effects are well described. Furthermore, we will defer the complex discussion on vitamin E acetate because it was discussed in other publications and is under investigation by the United States Food and Drug Administration [8, 10]. The following pesticides were not detected at the level of quantification (LOQ) of 0.065 ppm via LC-MS/MS: acetamiprid, aldicarb, azoxystrobin, carbaryl, carbofuran, chlorantraniliprole, fipronil, flonicamid, imidacloprid, metalaxyl, methiocarb, methomyl, thiacloprid, and thiamethoxam. Myclobutanil was not detected at the LOQ of 0.13 ppm.

Discussion

The recent epidemic of EVALI has become a public health concern. This manuscript is the first to provide a detailed report of the clinical course of adolescent patients with EVALI, their PFT results, and laboratory analysis of a vaping product. We believe the descriptions and analyses provided are helpful for healthcare providers, including medical toxicologists, and public health officials.

We present this case series as a representative presentation of the case series reported by Layden et al. [2], and the radiographic findings described by Henry et al. [9]. All three of our patients are considered a “confirmed case” as defined by Layden et al.; and all three were treated with glucocorticoids because an infectious source was not found [2]. We were unable to find in the published literature an EVALI case series in previously healthy adolescents with associated PFTs and product analysis. We were able to provide an in-depth and relevant description of the cases in this report because our team consisted of multiple specialists, and it was involved throughout the evolving clinical timelines for these patients.

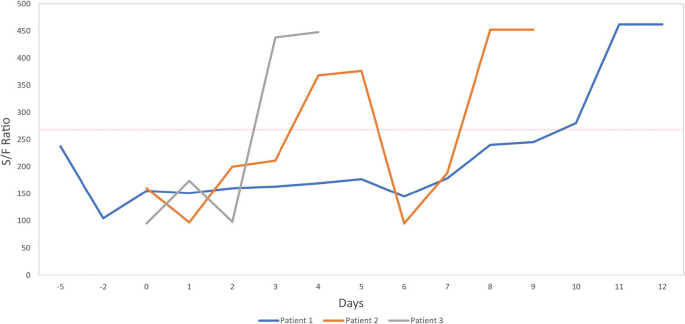

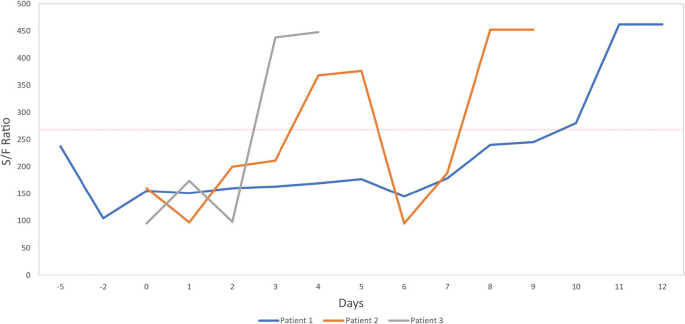

Our patients were all healthy adolescents without a prior history of known lung pathology, which demonstrates the progressive nature of this EVALI in healthy patients. We attempted to illustrate the progression of disease from the time of presentation to our institution to discharge using objective measures listed in Table 1. As oxygen saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen (S/F ratio) has been shown to correlate with partial pressure arterial oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FIO2) in the evaluation for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), we present the S/F ratio (Table 1, Fig. 2) to illustrate the level of pulmonary injury in these patients [11]. We also found an improvement of the S/F ratio (illustrated in Fig. 2) after initiation of high-dose methylprednisolone; though, it is impossible to prove that this improvement was not due to natural disease course.

Oxygen saturation/FiO2 (S/F) ratio trend across hospitalization. Trends illustrate time to improvement improved with earlier commencement of corticosteroids. Red-dotted line represents cut off for diagnosis for ARDS. Day 0, Day of methylprednisolone treatment initiation. Saturations were documented at 07:00 each day.

Discussion on Pesticide Components

There were three unfamiliar pesticides found on laboratory analysis which we believe are worth discussion: bifenazate, boscalid, and tebuconazole. Bifenazate is a carbazate miticide with a low likelihood of acute toxicity by any route of exposure [12]. The mechanism of action is still under investigation, but it appears it specifically inhibits the mitochondria of mites [13]. Boscalid is a commonly used fungicide that is considered nontoxic to terrestrial animals [12]; though, a basic science investigation suggested it can contribute to neurodevelopmental toxicity via oxidative stress [14].

Tebuconazole is an antifungal agent which might be relevant to the above cases. During the registered use of this product, it does not behave as a pulmonary toxicant. When heated to over 150 °C, tebuconazole decomposes to hydrogen chloride and multiple nitrogen oxide products (including nitrogen dioxide) [15,16,17,18]. Hydrogen chloride in this setting can produce chlorine gas which should not have delayed pulmonary effects but may explain a fleeting “burning” sensation our patient described; though, the product fluid was found to have a lower concentration than is considered a harmful hydrogen chloride concentration in the occupational setting. Nitrogen dioxide is a classic pulmonary toxicant known to produce delayed pulmonary effects including non-cardiac pulmonary edema and ARDS. In acute exposure, it is known to cause fever, anorexia, and lipid peroxidation seen on bronchoalveolar lavage [17]. This can contribute to lipoid pneumonia which has been reported by others [1]. Another nitrogen oxide is nitric oxide which plays an important role in gastrointestinal motility and dysmotility [19]. We propose that pyrolysis and inhalation of tebuconazole might have contributed to the initial burning sensation from chlorine gas, early gastrointestinal symptoms from nitric oxide, and delayed ARDS from nitrogen dioxide. The contribution of tebuconazole to EVALI remains to be determined through further work.

The above analysis should not be considered exhaustive due to the volume of sample which limited the number of possible analyses. Some states require regular testing for tebuconazole, and forbid the presence of tebuconazole, in regulated THC products [20, 21]. However, the manufacture source of the product we tested is unconfirmed. We provide these results as empiric data from a singular case and recognize that additional coordinated investigation into these products and the associated illnesses are needed to determine an etiology.

At this point, no one can definitively state whether EVALI will cause chronic, or delayed, lung pathology. All three patients had PFTs performed acutely, and two had repeat PFTs 1–2 months after injury. These results did not reveal clinically significant pathology in our three EVALI cases. Though we cannot speculate what may happen in the future, we hope the youth and prior healthy state of our patients is protective against delayed pulmonary effects.

Importantly, all three of our patients were regular users of THC-vaping devices and initially presented to an outpatient clinic. At each visit, influenza testing was negative, and the patient was given a prescription for antibiotics. It is unclear if these patients were asked about risk behaviors, specifically vaping, during those encounters. It is also unknown if these patients were evaluated in the presence of their caregivers or alone. Given the popularity among adolescents and adults for these products, along with the increasing incidence of EVALI, we feel it is imperative for all providers to consider vaping as part of the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with malaise, cough, and dyspnea, particularly if gastrointestinal symptomatology and hypoxemia is also associated with acute illness.

Conclusion

We hope this case series increases the awareness of healthcare providers to the initial clinical presentation, uncommon radiographic findings of the chest, and clinical course of patients with EVALI who survive to discharge from the hospital. We also hope this report can be used as a cautionary tale for providers while they (a) counsel their patients regarding these products, and (b) evaluate adolescents with vague respiratory symptoms more carefully until further understanding of their illnesses can be ascertained.